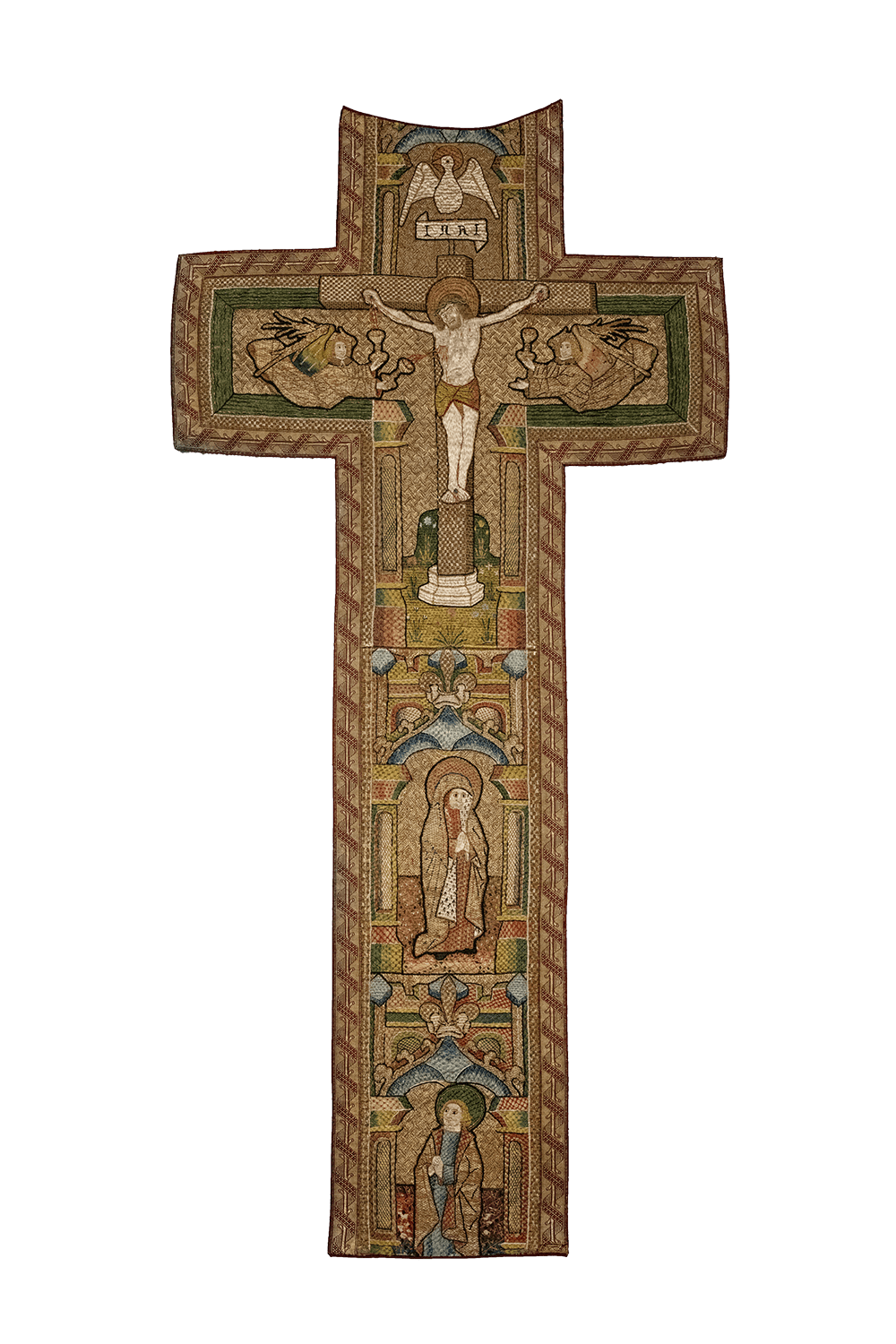

Two panels of opus anglicanum

The shapes of these embroidered panels (also known as orphreys) indicate that they once decorated the front and back of a medieval chasuble, a type of sleeveless liturgical vestment worn by members of the clergy as they perform Mass. They are remarkably vivid and colourful examples of a type of liturgical embroidery created by English workshops towards the end of the fifteenth century and more commonly described today as opus anglicanum, the Latin term for 'work of the English'. It is how English embroideries (both religious and secular in design) can be found documented in a number of important medieval sources from continental Europe, including in the inventories of great cathedral treasuries, the collections of the Catholic popes, and those of the nobility and monarchy of France. For example, according to the thirteenth-century chronicler Matthew of Paris, Pope Innocent IV had a particular passion for English embroideries. By the time our panels were produced, in around 1490, opus anglicanum was being bought in high volume by English churches too, and powerful religious figures such as the archbishop of Canterbury, Cardinal John Morton (c. 1420-1500), are known to have commissioned large suites of vestments for distribution to favoured churches and monastic foundations.

Our two panels differ in shape from one another, with a cruciform panel that would have adorned the back of the chasuble, and a narrow, rectangular counterpart made to cover the chest. The former of the two depicts the figure of Christ crucified on the cross between two angels who hold out chalices in order to collect the blood running from his nail wounds. Below him in individual architectural compartments are the Virgin, shrouded in an ermine-lined mantle, and Saint John who holds his hands clasped in a mixture of prayer and grief. Above Christ's head is a large, white, haloed dove, holding the titulum inscribed with the traditional letters INRI [Jesus of Nazareth, King of the Jews] in its claws. Its counterpart panel is embroidered with single figures standing, like Mary and John, in individual niches, and holding attributes that identify them as Saint James (with his pilgrim's hat and staff) at the top, and Saint Andrew (with his x-shaped cross) at the bottom. The central figure is somewhat androgynous in character, but may be intended to represent Mary Magdalene (holding an ointment pot with which she anointed Christ's wounds).

The vivid, shimmering effect made by the silks on both panels was achieved by laying unwound threads, also known as floss, across the surface of a stiffened linen support before couching them down in a few sporadic places, so that the fibres appear to float and billow from the surface. This was a time-saving exercise adopted by embroiderers of opus anglicanum in the latter half of the fifteenth century, but one that simultaneously created dazzling results. The silks and gold threads that cover every inch of these panels were ingeniously worked in ways that create incredible variations of texture, colour, and lustre. As a result, light flashes across their shimmering surfaces, which flare and recede as they move.

Layered vestiges of eighteenth and nineteenth century silk fabrics hidden under both panels' wide gold braiding, along with the shape of the cutaway neckline visible along their top edges, reveal the secrets of a long history of alteration and reuse, and though they are over 500 years old, it is clear that they remained in service well into the modern period.

Provenance

The Adler Collection, until;

Their sale, Sotheby's London, 24 February 2005, lot 67